- Home

- Blog Posts

- Building Belonging: How One School Leader Is Designing Schools for Equity, Welln...

Building Belonging: How One School Leader Is Designing Schools for Equity, Wellness, and Student-Centered Learning

Written by National Center on School Infrastructure (NCSI),

Representing diverse public sector voices from across the country, NCSI’s Advisory Committee members bring a wealth of expertise and experience from the field that has helped shape NCSI’s priorities. Over the course of this year, we are featuring Advisory Committee members speaking about insights gained through their work to drive school infrastructure improvements. Here we interviewed Jo Ann Armstrong, Chief Financial Officer at Belvidere Community Unit School District 100, Belvidere, IL, to hear about her work to advance design strategies that meet the emotional, social, and academic needs of all students.

In the small community of Belvidere, Illinois, Jo Ann Armstrong is redefining what it means to lead a school district. As the Chief Financial and Operations Officer for District 100, Armstrong wears many hats—and has taken on the challenge of transforming aging facility infrastructure, outdated school design, and inequitable access into an opportunity for meaningful change. At the heart of her work? A deep belief in social-emotional learning (SEL), inclusive school design, and creating environments where students feel they belong.

From HR to Holistic Change-Making

Armstrong has always been a proactive problem solver, an approach she has cultivated throughout her career in human resources, finance, and operations. Armstrong never wants to solve problems after they arise, instead of being able to help prevent them from happening. That lived experience informs her current emphasis on wellness—not only for students, but also for staff and the community at large.

When she joined Belvidere in 2022, she entered a district with 11 schools, an average building age of 42 years, and a long-standing habit of deferring maintenance. “They just kept saying ‘deferred,’ but we’re not supposed to defer until oblivion!” she jokes. With aging facilities, two schools still on well water, and some not fully ADA accessible, she knew the work ahead was more than just financial—it was foundational.

Reimagining Space, Reclaiming Purpose

Armstrong’s approach is strategic and grounded in research. After conducting a comprehensive needs assessment, she launched a 10-year capital plan to bring Belvidere’s buildings to a new level of performance—and more importantly, to reimagine them in ways that serve all students.

“We’ve changed the furniture, the color schemes, the lighting—everything,” she explains. Gone are the days of harsh primary colors and fixed rows of desks. In their place: natural tones, flexible learning spaces, and even atriums where students engage in hands-on greenhouse projects. “We brought the outside in,” she says. “Some of our science classes are actually out there learning in real time.”

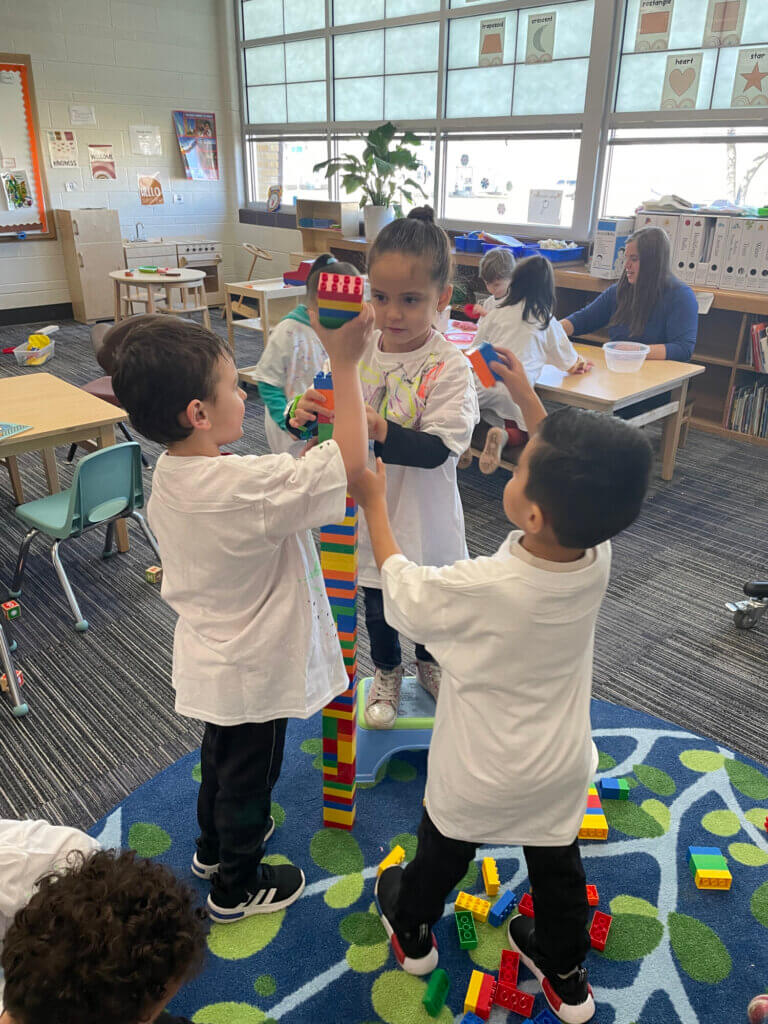

This transformation isn’t just aesthetic—it’s strategic. The district has embraced play-based learning for Pre-K through first grade, shifted to project-based instruction at its alternative school, and prioritized student wellness in its design choices. “We want our kids to feel like school is a place they want to be,” says Armstrong. That vision is working: chronic absenteeism dropped by 39% last year, a statistic that caught the attention of state officials.

A Blueprint for Equity

Equity is a guiding principle for Armstrong, who is acutely aware of the challenges posed by geographic and demographic divides. “We are very neighborhood-school oriented,” she explains, “and where you live can mean you go to a 127-year-old school or a much newer one.” The district serves a diverse and economically varied population—including migrant and transient families, and a growing number of students facing food insecurity. The district compiles community support resources to facilitate access for families in need.

One innovative partnership with the local Future Farmers of America chapter led to the planting of a small orchard, feeding students and families through a “community chest” model. Other schools host chicken coops, greenhouses, raised garden beds, and even technical education opportunities at a repurposed former shopping center. Students now graduate with certifications in welding, and new programs in nursing are on the way. “We served as project managers for the Advanced Technology Center and helped design that space ourselves,” she says proudly, “with exactly what our students would need to succeed right out of school.”

Systems Thinking and Sustainable Leadership

As the owner of the “Operational Resources” pillar in the district’s strategic plan, Armstrong doesn’t shy away from the logistical grit of her work. With 13 buildings and only five maintenance workers, she recently received approval to hire specialized tradespeople like an electrician and a plumber, and three certified HVAC technicians. Meanwhile, she’s overseeing the issuance of $22 million in Health Life Safety bonds to overhaul roofing, HVAC systems, and security infrastructure.

But her work extends beyond numbers and blueprints. She’s also focused on systemic resource sharing and policy advocacy. “I’d love to see more spaces where school leaders can go to find resources—not curriculum, we’ve got plenty of that—but real examples of what inclusive, student-centered classrooms look like,” she says. Through partnerships with consultancies such as BrainSpaces and the Donovan Group, she’s sought to fill that gap in the absence of consistent federal and state support.

Leading with Empathy, Learning Through Community

Whether it’s designing inclusive buildings or lobbying for categorical aid reform in Illinois, Armstrong grounds her leadership in empathy and collaboration. She taps into networks like the Association of School Business Officials (ASBO) and connects with neighboring districts to share insights. She also leverages national research firms to benchmark best practices.

Ultimately, Armstrong believes school design and social-emotional learning are inseparable. “We learned during COVID that kids don’t all learn the same way,” she reflects. “We’ve always known that, but the pandemic made it undeniable. And yet, we’re still trying to teach in buildings and with systems that weren’t built for today’s learners.”

Her vision? A public school system that’s resourced to meet the emotional, social, and academic needs of all students—and a community that sees its schools not just as places of instruction, but places of connection and care.

Jo Ann Armstrong’s work is a case study in what happens when operational leadership meets a deep commitment to student belonging. Through strategic planning, inclusive design, and a strong SEL foundation, she’s not just upgrading buildings—she’s reimagining what schools can be.