- Home

- Blog Posts

- “Castles, Not Prisons”: Guy Bliesner on the Role of School Security in Supportin...

“Castles, Not Prisons”: Guy Bliesner on the Role of School Security in Supporting Learning

Written by National Center on School Infrastructure (NCSI),

Representing diverse public sector voices from across the country, NCSI’s Advisory Committee members bring a wealth of expertise and experience from the field that has helped shape NCSI’s priorities. Over the course of this year, we are featuring Advisory Committee members speaking about insights gained through their work to drive school infrastructure improvements. Here we interviewed Guy Bliesner, School Safety and Security Analyst, Office of the State Board of Education in Idaho, to hear his perspectives on designing school safety measures that support the daily work of teaching and learning.

For Guy Bliesner, school safety isn’t just about video surveillance and “hardened” buildings. It’s about ensuring that every layer of security supports the ultimate mission of education. As Idaho’s award-winning school safety and security analyst, Bliesner brings a rare cross-disciplinary perspective to the national conversation on school infrastructure, safety, and learning. He doesn’t just assess threats—he connects the dots between access control systems and algebra class, between behavioral interventions and educational outcomes. “Safe places are generally secure places,” Bliesner explains. “So we look at it as a much more holistic process.”

Bliesner’s approach begins with a deep respect for the primary function of schools as places of learning. “Security is the protection of assets,” he explains. “And the first asset in schools has to be people. The second asset is the educational environment.”

Safety That Feels Safe

Bliesner pushes back on the current trend toward high-visibility security measures that may create unease rather than comfort. “You can have the perception of safety without safety. Conversely, you can have the perception of not being safe while being very safe indeed,” he says. But actual and perceived safety are equally important to creating a nurturing, productive learning environment. “What we need to do, using this holistic approach, is build a safe environment that is also perceived as such, so that we can move easily forward.”

This philosophy underscores his commitment to integrating security measures intentionally designed to support the daily work of teaching and learning, rather than relying on externally imposed security protocols that don’t work in real classrooms. “There’s an overwhelming pressure to say that classroom doors must be locked and closed during all instruction,” he explains. “But when I go into schools that try that, anytime anyone knocks on the door, the kid at the desk next to the door throws the door open without looking to see who’s knocking.” Bliesner observes similar challenges at school campuses with multiple buildings: exterior doors are often built for security, but there’s no effort to prevent teachers and students from propping the doors open to make it easier to dash between buildings.

The takeaway? Rules that interrupt the flow of the school day without genuine engagement from educators will be ignored—if not actively undermined.

Building Haven Spaces, Not Fear Factories

As Bliesner explains, there are a few generally accepted, highly effective foundational physical security practices and tools that should comprise every school’s starting place security profile. First, space must be securable space at two levels: the building envelope and at the classroom door. The locks, doors, windows, and fences, all the other “hard parts” that address daily operational needs have significant security implications. Even a school’s HVAC system has security considerations—if the HVAC system isn’t working properly to keep learning environments comfortable, the people within those environments are more likely to prop open doors and windows.

Second is effective communication, the ability to hear and be heard from all occupied spaces in a school. Communications systems, including a school’s public address, intercom, and telephone systems play an integral role in both daily and emergency communications. Relatedly, modern building automation systems that include access control and video surveillance capabilities ensure that information can be gathered and transmitted efficiently—whether that information is about a security threat or a burst pipe.

But security decisions also need to be highly specific to each individual school’s environment in order to support, rather than disrupt, teaching and learning. Instead of “hardening” schools, Bliesner advocates for creating environments that feel safe and supportive. “‘Hardening’ sounds like we’re creating a hard environment. That’s not it at all. What we’re doing is creating the shell that protects the school community and allows education to effectively take place inside it.”

Bliesner uses a memorable metaphor to distinguish his vision from more punitive models of school safety: “We don’t need prisons. We need castles.” He elaborates, “When you walk into that place, it has to be a sanctuary for the religion of education.”

Security, Support Systems, and the Whole School Community

Bliesner outlines four foundational elements of effective school safety: communication, behavioral threat assessment, simple emergency protocols, and a shared culture. “It’s hard enough to be a classroom teacher,” he emphasizes. “If anything is intrusive to the educational process, it will be ignored.”

That’s why he favors systems that are intuitive, unobtrusive, and integrated at the design level. Retrofitting, he notes, “is always a much more expensive process.” Fortunately, there is a growing body of available guidance for effective school physical security. The recently released P.A.S.S. K12 Guidelines Version 7 and ANSI-approved A.S.I.S. International School Security Standard provide excellent information on school physical systems and practices. Regardless of the framework a district adopts, Bliesner strongly recommends that stakeholders keep front and center the features and needs of each individual school.

Security, for Bliesner, can’t be siloed. It must include everyone who works in a school as well as members of the school’s broader community—from cafeteria workers to administrators to grounds crews to parents. “The community ethos has to be community-wide across all of those elements or it will fail.”

He also rejects the idea that school safety is solely about preventing high-profile events like school shootings. “The statistical reality is you are twice as likely to be struck by lightning as to be involved in a school shooting,” he points out. But threats like bullying, self-harm, and non-custodial abductions are far more common and equally deserving of attention.

Planning for Security, Designing for Trust

Bliesner’s message is simple but powerful: “Everything we do in one area has unintended downstream consequences.” That’s why he emphasizes collaboration, flexibility, and design that centers on human relationships.

In particular, integration of security features into school facilities’ master and capital improvement planning efforts can enhance the traditional focus of master planning—on student capacity, instructional spaces, educational adequacy, parking, aesthetics—with physical security. Elements of a school’s physical security should be considered a default component of a school’s educational adequacy. How can an educational environment be considered adequate if it is not both warm and dry and at the same time also both safe and secure?

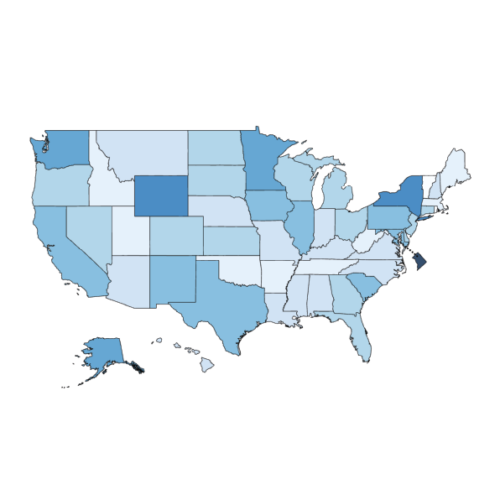

Implementation of modern physical security systems like access control and video surveillance lend themselves well to inclusion to the school design process for new construction and major renovation, as do inclusion of architectural design elements like single point entry and secure visitor entrances. Currently, most new construction and major renovation projects in schools include these elements with varying degrees of effectiveness.

But these elements matter for safety, for security, for comfort, and for achieving the ultimate mission of a school—nurturing highest quality teaching and learning. By placing security side by side with other elements, Bliesner explains, we can honor both goals: “When you walk into a place of learning, it has to be a haven space.”

In an era of increasing tension between safety mandates and learning environments, Bliesner’s insights offer a blueprint for how security can quietly—but powerfully—protect the heart of what schools are for.