- Home

- Blog Posts

- Healthy Schools, Healthy Communities: A Q&A with Dr. Erika Eitland

Healthy Schools, Healthy Communities: A Q&A with Dr. Erika Eitland

Written by National Center on School Infrastructure (NCSI),

The intersection of public health and the built environment is increasingly recognized as a determinant of health outcomes, particularly for historically marginalized populations. Yet, these two fields intersect infrequently and, at times, ineffectively. Erika Eitland, MPH, ScD, has made it her mission to remedy that challenge. She has built a career covering public health and architecture, working to ensure that school facilities support student and teacher well-being—particularly for populations often marginalized in traditional design processes.

As Director of Human Experience Research at Perkins&Will, Eitland has helped connect decades of research to practice, ensuring that buildings serve as catalysts for health and learning. In this conversation, she reflects on her path, the changing landscape of human-centered school design, and practical steps any leader can take to create an ethos of healthy buildings.

Q: You began your career in public health, not architecture. What brought you to the world of building design?

Eitland: Never in a million years did I imagine I’d be working at an architecture firm as my public health intervention. As an MPH candidate, I was studying climate and health, but I found myself constantly interacting with students from the School of Architecture. We were all talking about the same issues—climate adaptation and human well-being—but from totally different perspectives.

What struck me was that communities and people weren’t being centered in the design process, even though buildings were a central part of climate resilience. That realization catalyzed my thinking about how the built environment could contribute to human well-being and enhance our daily experience.

Public health and architecture define impact and outcomes in very different ways. What dots need to be connected to optimize school design to support student and teacher health?

Eitland: Buildings aren’t just bricks and mortar—they’re part of our public health infrastructure. During my time at Harvard’s Healthy Buildings program, my colleagues and I wrote Schools for Health: Foundations for Student Success, which brought decades of research together in one place.

Key findings from the Schools for Health report

- Healthy schools boost learning: Six environmental factors have positive impacts on student attendance, performance, and focus: IAQ, thermal comfort, lighting, acoustics, moisture/mold, and physical safety.

- Teachers benefit too: Better building conditions improve teacher health, satisfaction, and retention.

- Investments pay off: Even modest upgrades in ventilation or acoustics generate measurable academic and economic returns.

- Equity is at stake: Students in historically marginalized communities are more likely to attend schools with poor infrastructure, making facilities a key equity intervention.

- Policy gaps remain: The U.S. still lacks a systematic way to measure and ensure school building quality, despite decades of warnings.

We looked at things like ventilation and filtration, carbon dioxide levels in classrooms, green cleaning practices, how daylight and biophilia can reduce stress and absenteeism. I was connecting data that no one else had put together: the Massachusetts School Building Authority was tracking building quality, the Department of Education was tracking student outcomes, and the Bureau of Environmental Health was tracking asthma—but none of that linked together.

A big part of my work was taking this technical science and translating it for policymakers and school leaders so they could act on it. For me, that was the turning point: connecting hard data with advocacy. One day, I’d be with biostatisticians, and the next, I’d be at the statehouse talking with senators about why these issues matter. That experience convinced me that if we want healthy schools, we have to bridge science, design, and policy.

Q: How does the Human Experience Research Team approach design projects?

Eitland: Our Human Experience Research efforts are really about putting people at the center of design. Perkins&Will has always been known for its design excellence, but the Research Team exists to make sure that design decisions are grounded in evidence about health, equity, and human outcomes.

Our clients are mostly school districts, universities, healthcare systems, and civic institutions. They all share a responsibility to the communities they serve. That means the design process can’t just be about aesthetics or cost. It has to account for health, equity, and climate resilience.

For any new project, we start by listening and gathering data using tools as diverse as community surveys to environmental health indicators. We even created an open-source tool, PRECEDE (Public Repository to Engage Community and Enhance Design Equity), which helps analyze health risks, demographics, and environmental exposures around a project. We then use conversations with teachers, students, families, and facility staff to validate that information.

After we’ve developed a set of community-informed insights, we translate them into design strategies. The demands of the project and the needs of the community always dictate our designs, whether we’re integrating more daylight in classrooms, carving out spaces for wraparound services, or building HVAC infrastructure that reduces asthma triggers.

Q: You’re also a co-founder of CAUSE, the Coalition of Advanced Understanding of School Environments. What is it, and why is it important?

Eitland: CAUSE is unusual because it brings together multiple big firms—Perkins&Will, HKS, Multistudio, and others—alongside researchers and district leaders. In our industry, firms usually compete with each other, but CAUSE is open-source and non-profit by design. We wanted to create something consistent and accessible that anyone can use, not a proprietary product that gives one firm an advantage. In an industry built on competition, we’re proving that collaboration can accelerate impact.”

The coalition is developing systematic ways to measure school quality, which still doesn’t exist despite decades of government reports. We’re piloting teacher and student surveys, pairing them with spatial and environmental data, and creating protocols for post-occupancy evaluations. With over 50 advisors from policy, design, and research, CAUSE is validating that the tools we’re building are meaningful to the people who need them most.

Q: What does it look like in practice to make sure that school buildings support wellbeing for all students and educators?

Eitland: Schools serve students who are neurodivergent, food insecure, or living with chronic conditions, and yet facilities often aren’t designed with them in mind. Equity means ensuring there are wraparound spaces for uninsured families and making classrooms accommodating for neurodiverse learners.

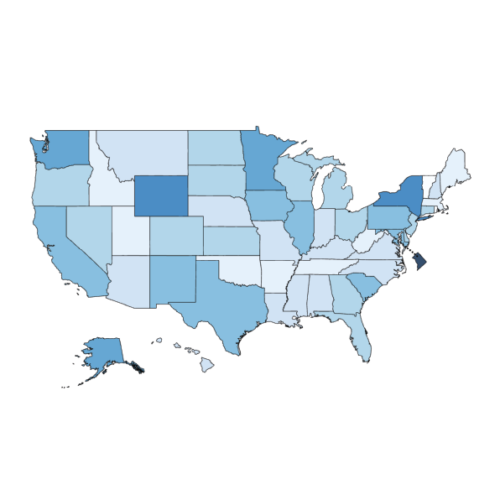

We also need to think about our schools in terms of their geospatial context. As a field, we need to take some time to understand how to support rural schools, which have a much lower concentration of community resources to draw from. Rural districts just don’t have the administrative bandwidth, volunteer base, or financial power of more populated suburban and urban districts.

And we have to consider the needs of our teachers as well, especially since so many K-12 teachers in the workforce are female. I’ve spoken with teachers who can’t even get a restroom break because the bathrooms in their school buildings are too far away from their classrooms. Basic building features like acoustics can create inequities—women educators often experience higher levels of vocal strain from speaking over ambient classroom noise. This leads to billions in lost productivity every year in the U.S. when teachers need to take a day off to treat a sore throat, not to mention the impact it can have on teacher burnout which, in turn, negatively impacts student achievement.

That’s unacceptable in 2025. Equity in school design has to include considerations of gendered realities, disability inclusion, and rural communities that often lack the advocacy infrastructure of urban districts.

I believe that design choices can either reinforce inequities or undo them. A school that ignores the needs of neurodivergent students, uninsured families, or women educators is perpetuating barriers to student learning and educator retention. But when we bring data and lived experience into the design process early, the building itself becomes a public health intervention. Our Human Experience Research exists to make that shift possible—and to prove that design is never neutral.

Q: What advice would you give to school and district leaders who want to foster healthier building design?

Eitland: First, recognize the vital role your facility manager plays. In many ways, a school’s facility manager does more for student health on a daily basis than a student’s pediatrician. Yet facility managers rarely get a seat at the table. Empower them, support their budgets, and involve them in new construction and operations.

Second, build transparency with your community. Walk your school board members and voters through your facilities. Let them see the restrooms, the mold, the windowless classrooms. Teachers and students know these issues, but voters need to see them firsthand to support investment.

Third, remember that small actions matter. Reduce visual clutter in classrooms. Provide circadian lighting, especially for high schoolers in the morning. Create spaces where students feel autonomy and care, whether that’s through thoughtful murals, biophilic design, or even rethinking vending machines to offer nourishing options.

Finally, remember that well-designed and maintained buildings are not a luxury, they’re a prerequisite for learning. Every child, every teacher, in every community deserves that.